The Lyme Controversy

The Quiet Epidemic just dropped on Amazon Prime, Apple TV, and Vimeo. This riveting documentary takes viewers on a journey through the history of Lyme disease and shares how effective diagnosis and treatments have been stonewalled by the scientific community, the American healthcare system, and even the federal government.

Since its discovery in 1975, Lyme disease has impacted the lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans—and those are the lucky ones who were able to get a diagnosis.

Due to its complexity, many Lyme patients struggle to resolve their symptoms and may go years without adequate treatment. One such patient’s story is told through this documentary.

Julia Bruzzese contracted Lyme as a child. Once an active, rambunctious child, Julia started feeling sick and quickly lost feeling in her legs.

For years, her family fought with doctors to understand what was wrong with her. Her health only seemed to improve through expensive antibiotic treatment. However, her doctors didn’t want to continue her treatments long-term and her health deteriorated.

At one point doctors, unwilling to accept a possible Lyme diagnosis, suggested that her paralysis was simply imagined. Julia, they said, was experiencing a psychotic episode and needed psychiatric treatment instead of life-saving antibiotics.

Julia’s insurance companies refused to cover her care and her family struggled to find Lyme-literate doctors who could provide treatment.

How could a disease be so prevalent and still be downplayed by medical professionals?

The answers may surprise you.

The Lyme controversy

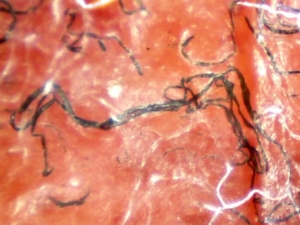

Lyme was first identified in 1975 as rheumatoid arthritis-like symptoms impacting children in rural Lyme, Connecticut. By 1982, researcher William Burgderfer, Ph.D., discovered that Lyme disease was caused by corkscrew-shaped bacteria, or spirochetes, spread through bites from infected ticks.

Lyme was first identified in 1975 as rheumatoid arthritis-like symptoms impacting children in rural Lyme, Connecticut. By 1982, researcher William Burgderfer, Ph.D., discovered that Lyme disease was caused by corkscrew-shaped bacteria, or spirochetes, spread through bites from infected ticks.

The disease rapidly reached epidemic levels as ticks carrying the disease have been identified across the continental United States.

Unfortunately, the disease spread while new laws and regulations changed the American approach to healthcare and research profitability.

Research and business

With the passing of the Bayh-Dole Act in 1980, universities and their faculty members could make patent claims on their discoveries made possible with federal funding.

This new legislation triggered the biotech boom almost overnight. By the 1990s, university scientists raced to patent genes, proteins, and even organisms so they could launch profitable products.

Researchers became entrepreneurs and stakeholders in biotech start-up firms instead of pure researchers with pure motives.

One product born of this patent sprint was a Lyme vaccine.

How vaccines work

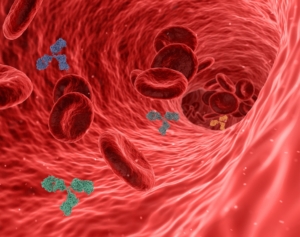

Most vaccines work like this: using molecular technology, a surface protein from a germ is multiplied and injected into the body. Immune cells find the foreign protein and create antibodies against it. If that germ later attacks, the body has antibodies at the ready to wipe the infection out.

Most vaccines work like this: using molecular technology, a surface protein from a germ is multiplied and injected into the body. Immune cells find the foreign protein and create antibodies against it. If that germ later attacks, the body has antibodies at the ready to wipe the infection out.

The underlying pathogen for Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, is a poor choice for vaccination. Unlike other pathogens we vaccinate against, B. burgdorferi can change its outercoat and “hide” from antibodies and the immune system.

Because B. burgdorferi can shape-shift and morph between tissues and over time, the patient’s immune system can’t keep up—and neither can a traditional vaccine.

A narrowing definition

Commercialization of Lyme disease through vaccine profits conflicted with patient interests in another way.

Patients with Lyme disease suffer from a wide variety of symptoms—the symptom list is 38 items long and includes symptoms such as joint pain, fatigue, fever, and headaches. Researchers needed to be able to tell if the spirochete had infected vaccine recipients through tick bites outside of test studies or were experiencing a severe side effect from the vaccine itself.

This distinction was vital if researchers wanted to earn FDA approval for their product.

So, researchers agreed to narrow the definition of Lyme disease, focusing on the tell-tale bullseye rash (which only manifests in 20% of patients) and limited blood testing, ultimately affecting many patients’ diagnoses. A narrower definition helped move the product past the FDA. However, accurately diagnosing Lyme became more complex as many different strains of the infecting spirochete were left out of Lyme disease testing.

Profitability through products

As the race for a vaccine intensified, major pharmaceutical companies dumped millions of dollars into vaccine research. Lyme researchers were also granted millions of dollars in federal funding. However, scientists quickly discovered that creating a Lyme vaccine wouldn’t be as cut and dry as they thought.

As the race for a vaccine intensified, major pharmaceutical companies dumped millions of dollars into vaccine research. Lyme researchers were also granted millions of dollars in federal funding. However, scientists quickly discovered that creating a Lyme vaccine wouldn’t be as cut and dry as they thought.

The infecting bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, was far more complicated than initially imagined. The unexpected complexity made finding appropriate proteins to use in the vaccine difficult.

Additionally, Lyme’s wide range of symptoms made it difficult for researchers to pinpoint whether vaccine recipients had a severe reaction to the vaccine or had contracted the disease from an unnoticed tick bite.

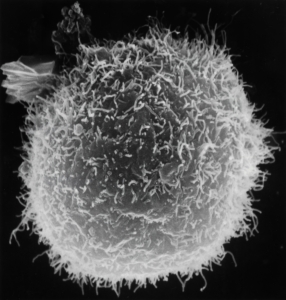

Western blot tests are traditionally used to identify Borrelia burgdorferi infections and diagnose Lyme disease. Western blots help researchers identify antibodies in patient blood samples from specific germs using a membrane strip that creates bands for each germ-related antibody present in patient blood samples. Patients typically need a series of bands for a positive result in their test.

Two of the most prominent bands on the western blot for Lyme were for OspA and OspB proteins. These proteins are universal across all strains of Borrelia burdgorferi and would signal infection in the western blot tests. However, as researchers developed an OspA-based vaccine, it was decided to remove the OspA bands from the western blots.

Researchers removed OspA bands from the western blot test because they needed to be able to tell between patients who had been vaccinated and those who had not. Vaccine recipients would always test positive for the OspA antibodies as OspA was the targeted protein in the vaccine—even if they weren’t infected with Borrelia burgdorferi.

Without the OspA and OspB bands in the Lyme western blot, it became harder for patients to get a positive diagnosis through blood testing despite experiencing an ongoing infection.

LYMErix

In 1998, the FDA approved the LYMErix vaccine, which went to market in December. By 2001, the FDA was flooded with complaints and lawsuits that LYMErix had harmed vaccine recipients. Instead of finding a miracle preventative measure, these early adopters wound up with symptoms that reflected serious Lyme complications.

In 1998, the FDA approved the LYMErix vaccine, which went to market in December. By 2001, the FDA was flooded with complaints and lawsuits that LYMErix had harmed vaccine recipients. Instead of finding a miracle preventative measure, these early adopters wound up with symptoms that reflected serious Lyme complications.

By 2002, LYMErix was pulled from the market, leaving people with a preventative mindset seriously injured by the vaccine instead.

While the mechanisms behind adverse LYMErix side-effects are still unknown, we’re no closer to having a Lyme vaccine than thirty years ago.

Even without a product to market, the definition of Lyme disease and how scientists test for it have not changed. Positive infection identification markers that were removed from the western blot test, such as OspA protein, haven’t been readmitted to diagnostic testing.

Researchers diligently worked to create a serological description for Lyme during the vaccine trials. However, the complexity of Lyme may have been too much to take on, leaving patients high and dry.

We’re left to wonder if the loss of profit potential in curing Lyme disease may play a role in the lack of continued vaccine research, diagnostic testing, and treatment options.

Thankfully, attitudes are changing primarily due to productions like The Quiet Epidemic hitting the mainstream media. Documentaries such as this trigger conversations about patient suffering, industry conflicts of interest, and the need for continued research.

As Lyme disease becomes more mainstream, we want to bring more attention to Morgellons disease, an illness triggered by Borrelia burgdorferi, the same spirochete behind Lyme. Our research, unlike profit-driven research from pharmaceutical companies, is driven by an intense desire to help people with Morgellons, and by extension Lyme disease.

Every dollar counts. Can you please donate as little as $50 today to help us fund the pure research necessary to better understand these insidious diseases and work toward a cure?

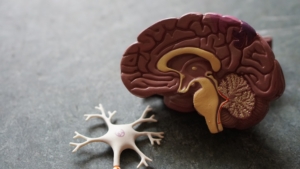

Unfortunately, encephalitis or swelling of the brain may cause only mild flu-like symptoms—if it causes any symptoms at all, making it difficult to detect. However, its impacts can be felt by patients who experience memory issues and struggle to focus on daily tasks.

Unfortunately, encephalitis or swelling of the brain may cause only mild flu-like symptoms—if it causes any symptoms at all, making it difficult to detect. However, its impacts can be felt by patients who experience memory issues and struggle to focus on daily tasks.

If you have Morgellons disease, the above description may sound too familiar. Many Morgellons patients haven’t even thought that fatigue and an inability to concentrate could be tied to a physical ailment that’s all too often categorized as a mental disease.

If you have Morgellons disease, the above description may sound too familiar. Many Morgellons patients haven’t even thought that fatigue and an inability to concentrate could be tied to a physical ailment that’s all too often categorized as a mental disease.  Fighting off an ongoing infection takes a lot of energy

Fighting off an ongoing infection takes a lot of energy Despite what the CDC and the mainstream media report, many studies have found that Morgellons patients suffer from an ongoing bacterial infection. Nearly all Morgellons patients have tested positive for

Despite what the CDC and the mainstream media report, many studies have found that Morgellons patients suffer from an ongoing bacterial infection. Nearly all Morgellons patients have tested positive for

Morgellons disease is a tick-borne illness caused by the same bacteria responsible for Lyme disease

Morgellons disease is a tick-borne illness caused by the same bacteria responsible for Lyme disease

Often, for patients who are diagnosed with Lyme shortly after becoming infected, a

Often, for patients who are diagnosed with Lyme shortly after becoming infected, a

Despite major breakthroughs in Morgellons research since 2012, there’s still debate over whether Morgellons disease is even legitimate. Please consider donating to the

Despite major breakthroughs in Morgellons research since 2012, there’s still debate over whether Morgellons disease is even legitimate. Please consider donating to the

The patient came to a Calgary clinic because she was experiencing

The patient came to a Calgary clinic because she was experiencing